Written by Jay Gribble, Health Policy Plus

It’s great to be at ICFP2018—so much going on and the conference hasn’t officially opened yet! Yesterday I had the chance to participate in a pre-conference session on the demographic dividend, and I must admit to being amazed at the progress that is taking place on helping countries think about how they are progressing toward a dividend. Yet among the discussion, I feel like there’s an important topic that is overlooked — the importance of addressing gender to maximize the opportunity to achieve a dividend. I had the chance to share a few thoughts at the end of the event, and I thought it was worth writing them down because gender and a demographic dividend are inextricably linked. I’m not a gender expert by any means, and most of my observations are little more than common sense based on years of writing and thinking about the demographic dividend.

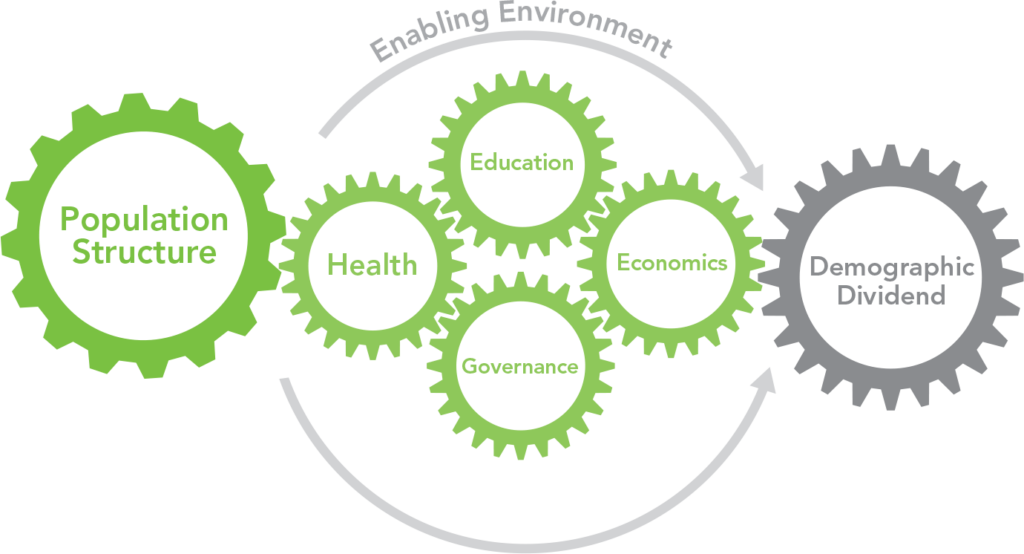

We always start talking about the demographic dividend with an eye on the population age structure—moving toward a larger working age population relative to the younger and older populations. And this is where family planning fits in—for though addressing fertility, countries are able to reconfigure their population age structure so that it has fewer dependents and more working age people. Yet, all too often, family planning is the woman’s responsibility. Where is attention to men? We know they are important, but without effectively changing the discussion about family planning, it will be difficult to change the gender dynamics around it, too. At the same time, biases against daughters results in their leaving school early, starting childbearing early, and even sex-selective abortion because son preferences. Addressing these types of gender biases is at the front of many FP/RH programs, and until we change them and make issues related to population age structure more gender equitable, achieving a demographic dividend will remain beyond the grasp of those who are working toward it.

We always start talking about the demographic dividend with an eye on the population age structure—moving toward a larger working age population relative to the younger and older populations. And this is where family planning fits in—for though addressing fertility, countries are able to reconfigure their population age structure so that it has fewer dependents and more working age people. Yet, all too often, family planning is the woman’s responsibility. Where is attention to men? We know they are important, but without effectively changing the discussion about family planning, it will be difficult to change the gender dynamics around it, too. At the same time, biases against daughters results in their leaving school early, starting childbearing early, and even sex-selective abortion because son preferences. Addressing these types of gender biases is at the front of many FP/RH programs, and until we change them and make issues related to population age structure more gender equitable, achieving a demographic dividend will remain beyond the grasp of those who are working toward it.

A healthy population is also critical to achieving a demographic dividend. Yet gender biases stand in the way of reaching a population as healthy as possible. When mothers have to get permission from their husbands to take children to health facilities, gender biases stand in the way of achieving a healthy population. When feeding practices result in daughters getting less food than sons, thereby missing opportunities for growth and development, gender biases are present. The prevalence—and in some cases, the acceptance–of gender-based violence contributes to poor health—physical, reproductive, and mental. Yet too many policies focusing on health fail to address the role that gender bias plays in trying to maximize the health and wellbeing of women and men, boys, and girls. Until countries address these issues, they won’t maximize the dividend they might have achieved.

An educated population is one on the most important inputs to a demographic dividend, because a population must be educated in order to move into higher-paying, more technical jobs that spur economic growth. Yet the fact that in most place, boys’ enrolment in school is higher than girls’—especially at tertiary and university levels—and this reflects a gender bias that impedes progress toward a demographic dividend. Similarly, comprehensive sexuality education can start with teaching boys and girls about the gender norms needed to accelerate economic growth and working to eliminate some of those beliefs that limit progress. Too many decision makers back away from this aspect of education, and the result is teenage pregnancy, girls dropping out of school, and a perpetuation of gender norm stereotypes. Fostering new ways of thinking and supporting educational opportunity for all children and young people is essential to harnessing a dividend.

Effective governance structures need to engage both women and men. Accountability mechanisms are needed to support implementing policies that have been developed, but that are falling short of achieving their policy goals. Women leaders at the community and national levels make tremendous differences, especially related to human capital formation. Countries have lots of laws, policies, and framework that should enable equitable participation in all aspects of civic life, but without political commitment and resources to carry them out, the efforts fall short of achieving their goals. When we hear about the good things women parliamentarians do for their constituents, I’m surprised that there aren’t more of them. But gender biases stand in the way—long-held thinking that men are more effective leaders than women undermines progress toward a demographic dividend.

And economic policies remain an area fraught with gender bias. A World Bank study found that 104 countries prevent women from working in certain jobs. Salary gaps, access to agricultural credit, inheritance and land rights are only a few ways that economic policies reflect gender biases and keep countries from achieving a dividend. According to the World Values Survey, much progress is being made in addressing gender equity, but one area continues to reflect an inherent gender bias: when jobs are scarce, more people believe that men have the right to a job more than women. Addressing this type of gender bias so that all people have access to employment on merit and skills rather than their sex, coupled with sound economic policies that advance economic growth and provide access to assets and credit for all people, are needed for countries to achieve a demographic dividend.

The demographic dividend is put forward as both a roadmap and a goal for helping countries move forward with economic growth. However, it relies on all people being able to contribute. If women and girls are restricted in what they can contribute, then the demographic dividend will remain elusive. Addressing gender norms in all pillars of the demographic dividend won’t necessarily lead to the desired goal of economic growth, but I’m confident that the potential growth will not be achieved unless leaders look at all inputs to a dividend with a gender lens. To decision makers who can turn the tide on this issue, my suggestion is don’t cling to a mistake just because you’ve spent a lot of time making it.

Jay Gribble, Deputy Director, FP/RH for Health Policy Plus and Senior Fellow at Palladium, has expertise in policy, research, and communication and more than 25 years of experience in international family planning.